Allan Smith MD, PhD

- Professor Emeritus

https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/people/allan-smith-md-phd/

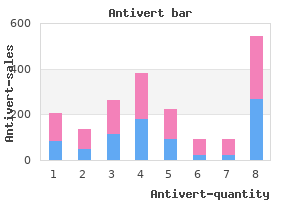

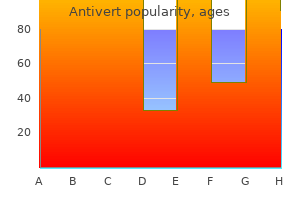

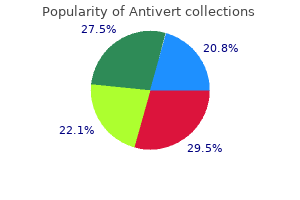

If medications names and uses purchase antivert with mastercard, however in treatment online antivert 25mg sale, the sources you suggested cannot account for the data medicine technology safe antivert 25mg, the restriction will result in a worse model? If your dataset is multimodal a dialogue box will appear asking to select the modalities for source reconstruction from a list symptoms anxiety discount antivert 25 mg amex. Once the inversion is completed you will see the time course of the region with maximal activity in the top plot of the graphics window. You will also see the log-evidence value that can be used for model comparison, as explained above. Critically this involves prompting for a time-frequency contrast window to create each contrast image. You will then be asked about the time window of interest (in ms, peri-stimulus time). If you just want to average the source time course leave that at the default, zero. If you specify a particular frequency or a frequency band, then a series of Morlet wavelet projectors will be generated summarizing the energy in the time window and band of interest. In the former case the time course of each dipole will be averaged, weighted by a gaussian. Therefore, if within your time window this time course changes polarity, the activity can average out and in an ideal case even a strong response can produce a value of zero. In the latter case the power is integrated over the whole spectrum ignoring phase, and this would be equivalent to computing the sum of squared amplitudes in the time domain. If you have multiple trials for certain conditions, the projec tors generated at the previous step can either be applied to each trial and the results averaged (induced) or applied to the averaged trials (evoked). Thus it is possible to perform localization of induced activity that has no phase-locking to the stimulus. The values of the exported images are normalized to reduce between-subject variance. Therefore, for best results it is recommended to export images for all the time windows and conditions that will be included in the same statistical analysis in one step. Note that the images exported from the source reconstruction are a little peculiar because of smoothing from a 2D cortical sheet into 3D volume. This could be improved by smoothing, but smoothing compromises the spatial resolution and thus subverts the main advantage of using an inversion method that can produce focal solutions. The group inversion can yield much better results than individual inversions because it intro duces an additional constraint for the ill-posed inverse problem, namely that the responses in all subjects should be explained by the same set of sources. The results for each subject will also be saved in the header of the corresponding input? There are separate tools there for building head models, computing the inverse solution and computing contrasts and generating images. In the case of the inversion tool group inversion will be done for multiple datasets. Within that structure, each new inverse analysis will be described by a new cell of sub-structure? For more details about the implementation, please refer to the help and comments in the routines themselves, as well as the original paper by [75]. This choice should be based on empirical knowledge of the brain activity observed or any other source of information (for example by looking at the scalp potential distribution). In general, each dipole is described by 6 parameters: 3 for its location, 2 for its orientation and 1 for its amplitude. This leads to relatively simple algorithms but presents a few drawbacks:??constraints on the dipoles are di? Through using Bayesian techniques, however, it is possible to circumvent all of the above limita tions of classical approaches. The head model should thus be prepared the same way, as described in the chapter 14. Since there are multiple local maxima in the objective function, multiple iterations are necessary to get good results especially when non-informative location priors are chosen. It is not possible to click through the image, as the display is automatically centred on the dipole displayed. The lower left table displays the current dipole location, orientation (Cartesian or polar coor dinates) and amplitude in various formats. This network model is inverted using a Bayesian approach, and one can make inferences about connections between sources, or the modulation of connections by task. In other words, one isn?t limited to questions about source strength as estimated using a source reconstruction approach, but can test hypotheses about what is happening between sources, in a network. This critical ingredient not only makes the source reconstruction more robust by implic itly constraining the spatial parameters, but also allows one to infer about connectivity. Two other contributions using the model for testing interesting hypotheses about neuronal dynamics are described in [77] and [33]. This interpretation of the evoked response makes hypotheses about connectivity directly testable. Importantly, because model inversion is implemented using a Bayesian approach, one can also compute Bayesian model evidences. These can be used to compare alternative, equally plausible, models and decide which is the best [78]. The second approach posits that each source can be presented as a patch? of dipoles on the grey matter sheet [28]. This spatial model is complemented by a model of the temporal dynamics of each source. Importantly, these dynamics not only describe how the intrinsic source dynamics evolve over time, but also how a source reacts to external input, coming either from subcortical areas (stimulus), or from other cortical sources. This order is necessary, because there are dependencies among the three parts that would be hard to resolve if the input could be entered in any order. For example, if trial 1 is the standard and trial 2 is the deviant response in an oddball paradigm, you can use the standard as the baseline and model the di? Alternatively, if you type -1 1 then the baseline will be the average of the two conditions and the same factor will be subtracted from the baseline connection values to model the standard and added to model the deviant. The latter option is perhaps not optimal for an oddball paradigm but might be suitable for other paradigms where there is no clear baseline condition. When you want to model three or more evoked responses, you can model the modulations of a connection strength of the second and third evoked responses as two separate experimental e? Under time window (ms)? you have to enter the peri-stimulus times which you want to model. You can choose whether you want to model the mean or drifts of the data at sensor level. Otherwise select the number of discrete cosine transform terms you want to use to model low-frequency drifts (> 1). You can also choose to window your data, along peri-stimulus time, with a hanning window (radio button). If you are happy with your data selection, the projection and the detrending terms, you can click on the > (forward) button, which will bring you to the next stage electromagnetic model. This is because tight priors on locations ensure that the posterior location will not deviate to much from its prior location. The prior location for each dipole can be found either by using available anatomical knowledge or by relying on source reconstructions of comparable studies. The onset-parameter determines when the stimulus, presented at 0 ms peri-stimulus time, is assumed to activate the cortical area to which it is connected. Because the propagation of the stimulus impulse through the input nodes causes a delay, we found that the default value of 60 ms onset time is a good value for many evoked responses where the? It is also possible to type several numbers in this box (identical or not) and then there will be several inputs whose timing can be optimized separately. This can be useful, for instance, for modelling a paradigm with combined auditory and visual stimulation. The duration (sd)? box makes it possible to vary the width of the input volley, separately for each of the inputs. In each of these matrices you specify a connection from a source area to a target area. For example, switching on the element (2, 1) in the intrinsic forward connectivity matrix means that you specify a forward connection from area 1 to 2. You can select the receiving areas by selecting area indices in the C input vector.

If the patients don?t know medicine dropper discount antivert 25mg fast delivery, what the reason of their complaints is medications 8 rights best antivert 25mg, the vestibular symptoms can provoke anxiety medications like lyrica discount antivert amex. Few years after the beginning of anxiety medications 4h2 generic 25mg antivert visa, we can suggest based on the case history that the organic vertigo was the trigger factor of the generalised anxiety disorder. Psychogenic superposition is suggested when there is a clear dissociation between objective and subjective disequilibrium, the patients complains severe rotatory vertigo without concurrent spontaneous nystagmus. In most of these psychogenic cases the vegetative symptoms associated to acute rotatory vertigo, like nausea and vomitus are missing. Anxiety can cause severe problems for example the patient cannot shopping, cannot use metro because the moving steps cause motion sickness and the metro is overcrowded. On the other hand, patient can use the latter at home for working, and can make excursions with bike. Alternatively, the psychosomatic mechanism might operate in such a way that the anxiety and panic increase vestibular responses to positional tests and caloric and rotational provocations. The vertigo Anxiety in Vestibular Disorders 209 treatment could be a longer process, than in non anxious patients, and needs more empathy from the doctor. Treatment of vertigo in patients suffering from anxiety disorders requires cooperation between neurootologist and psychiatrist. F& Franz B: Contemporary&Practical Neurootology, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Hannover, 2006. Eckhardt-Henn A, Best C, Bense S, Breuer P, Diener G, Tschan R, Dieterich M :Psychiatric co-morbidity in different organic vertigo syndromes. Holmberg J, Karlberg M, Harlacher U, Rivano-Fischer M, Magnusson M: Treatment of phobic postural vertigo. A controlled study of cognitive-behavioral therapy and self-controlled desensitization. Salhofer S, Lieba-Samal D, Freydl E, Bartl S, Wiest G, Wober C : Migraine and vertigo-a prospective diary study. Introduction Posturography is useful for investigating global balance performance (Kushiro & Goto, 2011). We found that anxiety affects postural perturbation in the anteroposterior axis, possibly indicating that anxiety affects the interactions between visual inputs and vestibular as well as somatosensory inputs in the maintenance of postural balance in patients complaining of dizziness (Goto et al. Dizziness is a common somatic complaint that can be caused by several factors including peripheral or central vestibular dysfunction. Anxiety and depression are closely related to somatic complaints, including dizziness. Patients can present with dizziness even in the absence of any signs of organic or functional dysfunction; such patients are usually diagnosed with psychogenic dizziness. The aim of our study was to identify abnormal findings in patients with psychogenic dizziness. Healthy subjects with high anxiety are reported to have larger sway in the anteroposterior axis (Wada et al. It is believed that anxiety affects the postural sway of the anteroposterior axis and the interactions of visual inputs with vestibular and somatosensory inputs are influenced by anxiety in healthy subjects (Wada et al. Maki and McIlroy (1996) reported that healthy subjects with elevated levels of state anxiety undergoing cognitive tasks such as mental arithmetic tend to lean forward. This observation shows that elevated levels of state anxiety cause the center of gravity to shift forward. We previously reported a clear relationship between anxiety and anteroposterior perturbations (Goto et al. There are several types of patients with vestibular disorders due to organic and psychogenic factors and combinations thereof. There may be some specific pattern of posturography depending on the levels of anxiety and vestibular deficits. It would be useful to know if there is a relationship between anxiety and postural sway in patients complaining of dizziness. Therefore, the relationship between the levels of anxiety and postural sway in patients complaining of dizziness was evaluated. Posturography is a useful tool for investigating the effects of various conditions (Kushiro & Goto, 2011), and we used it to evaluate postural sway. Methods the subjects were patients who visited Hino Municipal Hospital complaining of dizziness from January 2007 to May 2007. Before each examination, the purpose and procedure were explained and informed consent was obtained from each subject. Some patients required bithermal caloric tests, vestibular evoked myogenic potentials, auditory brain stem response, and head imaging. If no apparent organic or functional abnormalities were identified from a variety of examinations, the patients was were diagnosed with psychogenic dizziness. Patients were asked to stand on the platform with their feet parallel, gazing at a visual target: a black circle 17 cm in diameter on a white background fixed at a 1-m distance at eye level. Results There were 16, 25, and 13 subjects in the psychogenic, organic, and psychogenic + organic groups, respectively. However, this difference was Significant Posturography Findings in Patients with Psychogenic Dizziness 213 the perturbation of anterio-posterior direction is defined as Y and left-right direction is as X, respectively. This means that the patients with psychogenic dizziness became more stable in anteroposterior direction with their eyes closed. Discussion We tried to identify specific posturography findings in a variety of patients complaining of dizziness. It is believed that the effect of the organic disorder is so significant that the effect of anxiety on postural perturbation cannot be determined. This might be a clinical indicator of anxiety in patients with dizziness lacking organic and functional dysfunction. Since anxiety is closely related to vertigo and dizziness, it is important to evaluate anxiety in patients reporting dizziness. To obtain an accurate diagnosis, it is important to examine patients from both physical and psychiatric perspectives. Doctors in otolaryngology departments are familiar with routine physical examinations such as posturography and audiometry. However, they are not accustomed to evaluating the psychological status of patients. The only way to measure psychogenic status, including anxiety and depression, is to use self-rating questionnaires. Although these questionnaires are subjective measurements, it is not common to use them for evaluation. In both healthy subjects and patients experiencing dizziness, anxiety affects posturography in the anteroposterior direction. If patients do not have any functional or organic abnormalities, it is a diagnostic dilemma as to why they have psychological dizziness. The diagnosis of psychological dizziness is quite important, because if the patients have it, treatment should be specially arranged. In some cases, psychotherapy such as autogenic training can be successfully used to control anxiety (Goto et al. Power spectrum analysis clearly demonstrates that the effect of visual input on vestibular and somatosensory inputs is affected by anxiety. This research sheds new light on the mechanisms of dizziness and initiates the development of novel, promising diagnostic strategies. Psychiatric morbidity in patients with peripheral vestibular disorder: a clinical and neuro-otological study. Effect of anxiety on antero-posterior postural stability in patients with dizziness. Screening for adjustment disorders and major depression in otolaryngology patients using the hospital anxiety and depression scale. The effect of anxiety on postural control in humans depends on visual information processing. Anxiety affects the postural sway of the antero posterior axis in college students. Introduction Epilepsy is a heterogeneous entity with enormous variation in etiology and clinical features and is defined as two unprovoked seizures of any type (Waaler et al. Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders in pediatric and adult population (Moshe et al. Research in the past 20 years showed that the patients with epilepsy commonly have coexisting psychiatric conditions including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Garcia Morales et al.

While expectations and sensitivities vary from one individual to another medications used for depression purchase antivert 25 mg fast delivery, they seem to be particularly elevated in individuals with panic disorder medications kidney stones buy 25 mg antivert amex. Expectancy theory further postulates that anxiety expectancy stems from learned experiences that a given stimulus will generate anxiety or fear (Reiss & McNally treatment 2 stroke buy genuine antivert line, 1985) medications adhd cheap 25mg antivert visa. Nevertheless, a person need not experience anxiety in a particular situation in order to anticipate it. Certain situations may come to be associated with fear or anxiety after an individual has witnessed someone having a panic attack. Conversely, it is believed that anxiety sensitivity may be developed through learned experiences (Donnell & McNally, 1990) and inherited through biological factors (Reiss & McNally, 1985). For instance, although Donnell and McNally (1990) found that participants with high anxiety sensitivity were more likely to have experienced both a personal and family history of panic, two-thirds had never suffered a panic attack. In addition, findings from a retrospective study on the origins of anxiety sensitivity suggested that participants with high levels of anxiety sensitivity may have learned to catastrophize about the occurrence of bodily symptoms through parental reinforcement of sick-role behavior related to physical symptoms rather than anxiety-related symptoms (Watt et al. Schmidt and colleagues (1997) also revealed that anxiety the Differential Impact of Expectancies and Symptom Severity on Cognitive Behavior Therapy Outcome in Panic Disorderwith Agoraphobia 261 sensitivity predicts the development of panic and other anxiety symptoms independent of history of panic and trait anxiety. Thus, anxiety sensitivity is not considered a consequence of experiencing a panic attack, but rather a predisposing bio-psycho-social factor to developing panic. This suggests that an individual who experiences a panic attack but does not develop panic disorder may not have the biological markers nor the psychological and social attributes to developing panic disorder. Several studies have demonstrated that a greater association exists between anxiety expectancy and avoidance behavior, rather than with the occurrence of panic attacks and avoidance. Treatments aimed at diminishing the expectation of anxiety may also be effective in reducing the amount of fear actually experienced by the individual. For instance, Kirsch and colleagues (1983) succeeded in diminishing the amount of fear experienced in snake phobic patients through systematic desensitization and through an expectancy modification procedure. They concluded that the level of fear experienced by individuals with a snake phobia varies as a function of anxiety expectancy. Southworth and Kirsch (1988) also found that when the expectations of the occurrence of anxiety are reduced, patients with agoraphobia experienced less fear. These findings suggest that when clients expect to experience anxiety and they do not after several sessions of exposure, their fear ultimately diminishes. Earlier studies on the effects of expectancies on outcome mostly focussed on prognostic expectations. However, in a review on psychotherapy, Perotti and Hopewell (1980) concluded that although expectancy effects are important in various interventions including systematic desensitization, pre-treatment expectations have little effect. Measuring expectations both at pretherapy and during the early treatment phase may not only provide information on whether clients can change their expectations but it may also shed some light on the impact these cognitive shifts have on outcome. After several sessions of therapy, expectations may shift towards a positive direction if clients perceive improvement or they may shift towards a negative direction if no benefits are noticed (Weiner, 1982). However, there is a paucity of data examining the differential effects of distinct types of expectancies. Studies examining possible predictors in treatment outcome have determined that pre-symptom severity has an impact, especially pre-treatment agoraphobic avoidance and longer duration. However, no study to our knowledge has examined the differential impact of symptom severity and expectancies on cognitive-behavior therapy outcome of panic disorder with agoraphobia. First, we examined the impact of different types of expectancies on pre-treatment symptom severity. Expectancies that were examined included anxiety sensitivity, anxiety expectancy and prognostic expectancy as measured by avoidance expectancy. Symptom severity was measured in terms of frequency of catastrophic cognitions during a panic attack, degree of fear of symptoms already experienced during a panic attack, panic symptomatology, avoidance, and by depressive symptoms. It was predicted that the severity of baseline expectancy would be associated with baseline symptom severity. Second, we examined the impact of the initial treatment phase scores in contrast to baseline scores on outcome. With respect to symptoms, our hypothesis is consistent with theories on in-session change in cognitive-behavior therapy that suggest that shifts in symptoms during sessions are better predictors of outcome than pretreatment severity (see Muran et al. We predicted that initial treatment phase symptom scores would be better predictors of outcome than baseline scores. With respect to expectancies, it was hypothesised that early treatment phase scores would be better predictors of outcome than baseline. After being exposed to several components of therapy, it is assumed that participants will adjust their expectations to be more consistent with the information received in the first few sessions. Twenty-three participants were recruited from two specialised outpatient anxiety disorder clinics in Montreal: the Douglas Hospital Anxiety Clinic (n = 8) and the Centre for Intervention for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy at Louis-H. The remaining participants were recruited from advertisements in the local newspapers (n=26). Exclusion criteria included: (a) the presence of substance-related, psychotic and bipolar disorders and any organic brain conditions as evaluated by the psychiatrists; and, (b) the presence of any unstable medical condition considered by the evaluating psychiatrist to be mistaken for anxiety symptoms. Twenty-four patients also met criteria for one or more of the following secondary diagnoses ranging from moderate. Participants accepted in the study with a secondary diagnosis had disorders that were not in immediate need of treatment as assessed by the psychiatrists. Medication needs of the patients were evaluated during the evaluation with the psychiatrist. Participants under pharmacological treatment for anxiety, at the time of the evaluation, were permitted to participate only after medication had been stable for 6 weeks prior to treatment. Participants were asked to maintain the same dosage throughout the treatment phase of the study to allow for evaluation of the effects of psychotherapy above the effects of these drugs. Participants taking medication were not asked to discontinue pharmacotherapy before treatment since (a) many individuals would probably not participate because they would not want to stop taking their medication before treatment, and (b) discontinuing medication during treatment may lead to an increase in panic attacks which may affect responses given on baseline measures (Ost & Westling, 1995). All therapists followed a written manual which included the protocol for each session. The treatment consisted of 14 weekly, 3-hour sessions and comprised five major components: (a) education and information concerning the nature, etiology and maintenance of panic; (b) cognitive restructuring (Beck, 1988) aimed at demystifying symptoms and fears and helping participants identify, monitor and change mistaken appraisals of threat that precipitate panic attacks and maintain avoidance behaviors; (c) training in diaphragmatic breathing as a way of reducing physical symptoms that often trigger panic attacks; (d) interoceptive exposure exercises designed to reduce fear of somatic sensations through repeated exposure to bodily sensations associated with panic; and (e) prolonged and repeated in vivo exposure to feared situations. The following measures on symptom severity have demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties. The psychometric properties of the French-Canadian versions employed in this study are equivalent to those of the English version (Stephenson et al. Psychometric properties of the French-Canadian version have been found to be similar to those of the English version (Stephenson et al. This 21-item questionnaire, rated on a 4 point scale, examines the degree to which participants were affected by their symptoms over the past week. The following expectancy measures have not yet been validated for their psychometric properties. Participants rate on a scale of 0 (never) to 4 (very likely) how much they expect a future panic attack to occur in a particular situation regardless of whether or not they have previously experienced a panic attack in that situation. Internal consistency of the French version (Belanger & Katerelos, 1998) of this the Differential Impact of Expectancies and Symptom Severity on Cognitive Behavior Therapy Outcome in Panic Disorderwith Agoraphobia 265 questionnaire using the current sample was estimated at. It measures fear of anxiety and has been specifically associated with agoraphobia (see Taylor, 1993). The items assess the level of expected somatic, psychological or social harm that may occur as a result of anxiety symptoms. However, a history of panic attacks is not an essential component for developing negative beliefs about the harmful effects of anxiety. Psychometric properties of the French-Canadian version have been found to be similar to those of the English version (Marchand et al. However, the adapted version contains questions reformulated into expectancies. With the current French sample and with the items reformulated into expectancies, internal consistency when alone was at 95. Those who were considered appropriate for the study were invited to one of the clinics to take part in a structured interview. Those who did not meet the criteria of the study were appropriately referred elsewhere. Expectancies were assessed prior to therapy (T1) and after patients had completed 4 sessions (T2; initial treatment phase). Symptom severity was measured prior to therapy (T1), 4 sessions after therapy had begun (T2; initial treatment phase) and after the last session (T3). In addition, analyses of variance did not reveal any significant differences between those who took medication and those who did not on gender, sociodemographic variables, pre-treatment expectancy measures nor on most symptom severity measures (p >.

Both active interventions were manual-based medicine 2015 25 mg antivert otc, consisted of weekly 2-hour sessions over 8 weeks medications memory loss order cheapest antivert, and were designed to be comparable in terms of structure and clinician contact time schedule 8 medicines buy 25 mg antivert free shipping. Although follow-up data were not available for the control group treatment ringworm generic antivert 25mg with visa, both anxiety and worry symptoms continued to decrease significantly at each follow-up time point for both active intervention groups. There were no significant between-group differences at either follow-up time point. All participants underwent a social stress test before and after treatment which included an 8-minute public speaking task followed by a 5-minute mental arithmetic task. The stress management intervention consisted of eight weekly 2-hour group lecture-style sessions, with one 4-hour physical health and wellbeing speciality class. Both groups demonstrated statistically significant improvements on all outcome measures including anxiety symptoms, sleep quality, and stress reactivity as measured by the social stress test. The intervention for both groups consisted of 30 weekly 50-minute sessions carried out according to treatment manuals. Both active interventions consisted of eight text-based treatment modules delivered on a weekly basis over 8 weeks. In both interventions, participants were required to submit writing tasks to clinicians for feedback on a weekly basis. However, compared with behaviour therapy for short-term remission, the effect size was reduced to small. Compared with applied relaxation, a large effect size in favour of short-term psychodynamic therapy was found in terms of short-term improvement and remission; however, this was based on only one study. There were no significant differences between group therapy and the alternative treatments as a whole. However, only a small number of studies were identified for each type of alternative treatment. Follow-up data were available for three studies only, and therefore data were not able to be analysed by meta-analysis. Courses included five lessons delivered online over 8 weeks, and shared the same overall format. Participants in the clinician guided condition received weekly telephone or email contact designed to be approximately 10 minutes per contact. The intervention consisted of eight, twice weekly sessions lasting between 90 and 120 minutes over a 4-week period. Treatment gains for the intervention group were either maintained or further improved at the 6-month follow-up across all primary and secondary outcomes. The psychodynamic therapy intervention comprised 24 x 50-minute sessions twice-weekly over a period of 12 weeks. However, this difference was no longer significant at 6-month follow-up, with treatment effects remaining large and comparable for both groups. Seventeen of the original 23 participants completed the 1-year follow-up assessment. Fifteen of the 17 participants who were assessed at follow-up no longer met diagnostic criteria for panic disorder. Participants were split into nine groups, with up to eight participants in each group. Twenty-seven participants were excluded from the analysis because they failed to attend at least seven sessions. Large within-group effect sizes were demonstrated from pre to post-treatment for panic and depressive symptomatology, and there was a medium effect size for the measure of intolerance of uncertainty. Participants received on average three therapy sessions, and 46% of the studies used only one session of treatment. Compared with nonexposure treatments, exposure-based treatments led to significantly greater improvement in symptoms at both posttreatment and follow-up, with medium effect sizes observed. Furthermore, exposure treatments augmented with cognitive interventions did not outperform exposure treatments alone. Although single-session treatments were effective, a greater number of treatment sessions was associated with more favourable outcomes. The exposure interventions ranged from a single 3-hour session to six 1-hour weekly sessions. Only articles that included adult samples were included in the summary of findings. A medium effect size was found in favour of multiple sessions of in-vivo exposure at posttreatment compared with single sessions; however, this was no longer significant at 1-year follow-up. Compared with exposure alone, a large effect size in favour of applied tension was found for reducing fainting at both posttreatment and 1-year follow-up. Participants were familiarised with the programs before beginning exposure according to their unique treatment condition. All three conditions demonstrated significant and large within-group treatment effects across all outcome measures from both pretreatment to posttreatment and at 1 year follow-up, although the effects were smaller at follow-up. A medium effect size was found in favour of psychodynamic therapy compared with waitlist. Combined psychological and pharmacological treatments produced large effect sizes. However, there was no evidence to suggest that combined treatments were more effective than were either alone. Participants in the two active conditions received 12 weekly manualised 1-hour treatment sessions, matched on number of sessions devoted to exposure. Clinicians completed follow-up booster phone calls (20?35 minutes? duration) once a month for 6 months following the 12-week treatment period. Effect sizes for both groups were large compared with waitlist control participants. The interventions both consisted of 12 weekly 2-hour group sessions plus a brief check-in at 3-month follow up. There were no significant between-group effects on any measure for the intervention groups. The smartphone application corresponded to the content of the eight modules and could be used to complete homework tasks/exercises and to rate mood. Participants were encouraged to complete one module per week, but had 10 weeks to complete treatment. The clinician support consisted of twice-per week feedback for a total of 15 minutes per participant per week to support treatment progress sent via the smartphone application. The two intervention conditions received 16 weekly manualised individual therapy sessions of generally 50-minutes? duration, with a booster session 2-months posttreatment. Large effect sizes were found for both intervention groups compared with the waitlist group. Cognitive therapy was significantly more effective than was interpersonal therapy at both posttreatment and follow-up, with small to medium effect sizes found across measures at both time points. Treatment outcomes were maintained at follow-up, with no significant differences from posttest to follow-up. Both active interventions were manualised and involved up to 25 individual 50-minute sessions delivered on a weekly basis. In the current review, there was insufficient evidence to indicate that any of the other interventions were effective. Active treatment conditions as a whole produced large within-group effect sizes at both posttreatment and follow-up. Furthermore, compared with antidepressants, psychological interventions were associated with a significantly larger reduction in mean scores. It is important to note that in the majority of cases, participants were permitted to continue any antidepressant medication throughout studies in which psychological interventions were the active intervention. Studies were classified and analysed depending on amount of therapeutic contact (minimal contact, predominantly self-help, and self-administered) and therapy type (bibliotherapy, internet-based, computer-based). One study included young people aged less than 16; however, the meta-analysis produced comparable results when this study was removed from the analysis. Significant between-group differences were also noted for self-reported measures of depression and cognitive biases in favour of the intervention group. Participants in the fluvoxamine group were monitored by a psychiatrist and received 50 to 300 mg of the medication for 10 weeks. Family members of the participants were randomly allocated to a brief manualised family intervention or no treatment. Most family members were spouses/partners (72%), but there were also parents (22%) and siblings (6%). No significant between-group differences were found at Weeks 4 or 25, although the difference approached significance in favour of the intervention group at Week 25.

Mitten (1992) symptoms heart attack women antivert 25 mg low cost, Hendee and Brown (1987) treatment of tuberculosis buy antivert 25mg low cost, and Ewert (1982) treatment 5 alpha reductase deficiency order antivert online pills, all reported that women who participate in outdoor programs will often increase self-esteem and discover a sense of empowerment medications while pregnant purchase antivert american express. Mitten (1994) and Jordan (1992) noted that some outdoor education experiences increase physical and psychological stress and may actually be harmful to the emotional well-being of female participants. Jordan (1992) states that outdoor education programs focus on physical challenges which are geared toward the male psyche. Research by Kaplan and Talbot (1983) reported that focus on intense physical challenges detach participants from their environment, resulting in feelings of alienation and resentment. Female outdoor education programs were developed in an attempt to eliminate the barriers for women participating in traditional male activities. Researchers Thomas and Peterson (1994) and Wilson (1994) discovered that women enjoyed the opportunity to participate in outdoor activities without the intimidation that they felt would be present in a mixed-gender setting. The weakness of both of these studies is that women participated in a single sex outdoor program and then projected what their feelings would have been if men were present. Consequently, although research indicates that single gender programs are more strongly supported by data, investigation into the extent which constraints truly exist is warranted. Culp (1998) performed one such study and found that co-educational outdoor education programs primarily focus on the opportunity for social intermingling. Should this be factual among all female participants of outdoor education programs, co-educational programs may actually impede the potential growth of all female participants, yet in the same study some female participants of single gender programs expressed frustration at the stereotype that girls are not interested in competition? (Culp, 1998, p. Conclusion this chapter has provided a comprehensive review of the literature related to body image and its constructs. Relevant topics of interpersonal, intrapersonal, and social factors which influence body image in women were covered as essential components to the development of this study. Concepts as they relate to body image and physical and emotional well-being were explored in detail. Potential causal factors for body image dissatisfaction as it relates to current trends in society were discussed. A search stating how fitness relates to body image was revealed, and a critical view of the possible negative consequences of outdoor education programs on women was provided. These topics are influential factors in the development, prediction, and renovation of body image in women, and are crucial elements which are specific to this study, as well as to the expansion of research in this field. Relations of strength straining to body image among a sample of female university students. Perceptions of physical attractiveness among college students: Selected determinants and methodological matters. The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A meta-analysis. Body weight and body image among college women: Perception, cognition, and affect. The eating disorder sourcebook: A comprehensive guide to the causes, treatments, and prevention of eating disorders. Adolescent girls and outdoor recreation: a case study examining constraints and effective programming. Body image and body shape ideals in magazines: Exposure, awareness, and internalization. Effects of selected physical activities on health-related fitness and psychological well-being. The effect of television commercials on mood and body dissatisfaction: the role of appearance-schema activation. Adventure education and Outward Bound: Out-of-class experiences that have a lasting effect. How wilderness experience programs work for personal growth, therapy and education: An explanatory model. In the highest use of wilderness: Using wilderness experience programs to develop human potential. The effects of guided systematic aerobic dance programme on the self esteem of adults. Effects of wellness, fitness, and sport skill programs on body image and lifestyle behaviors. Negative body image and disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents: What places youth at risk and how can these problems be prevented? Firm but shapely, fit but sexy, strong but thin: the postmodern aerobicizing female bodies. Body image and body valuation in female participants of a wilderness adventure program. Self-objectification and esteem in young women: the mediating role of reasons for exercise. Exercise motivation, eating and body image variables as predictors of weight control. The effects of weight training and running exercise intervention programs on the self-esteem of college women. Television and adolescent body image: the role of program content and viewing motivation. The effects of exercise on body satisfaction and self-esteem as a function of age and gender. Effects of a circuit weight-training program on the body images of college students. I am: Female Male Please list in order (1-5) the value that you place on each of the characteristics pertaining to your body (1 being the most important, 5 being the least important) Appearance Sexual Attractiveness Fitness Mobility Health Continue to the next page. She is a graduate student at the State University of New York, College at Cortland, who is currently working on her Master of Science in Education. This survey will ask for student opinions on what they value about their body, and how they feel about their body. The survey will be given at the beginning and at the end of your education experience. That page will be removed by you and you will only be identified by number on subsequent pages. We do not anticipate that you will experience any discomfort from involvement in this research. All student responses will be combined, so no one will know which student gave which answers. Any information that may identify a student will be removed at the conclusion of the study. We hope that the results of this study will benefit the field of physical education by identifying the impact that this course may have on body image. Upon completion of the thesis, the combined results of this study may be shared with teachers, and other researchers through professional venues. Should you have any questions about this research, please contact the researchers at any time, Jody L. You will not lose any benefits you may be receiving if you decide not to participate. I acknowledge that I understand the explanation of this research study and I agree to participate. Higher scorers fell mostly positive and satisfied with their appearance; low scorers have a general unhappiness with their physical appearance. High scorers place more importance on how they look, pay attention to their appearance, and engage in extensive grooming behaviors. Low scorers are apathetic about their appearance; looks are not especially important and they do not expend much effort to look good. High scorers regard themselves as physically fit, in shape?, or athletically active and competent. High scorers value fitness and are actively involve in activities to enhance or maintain their fitness. High scorers value fitness and are actively involved in activities to enhance or maintain their fitness. Low scorers do not value physical fitness and do not regularly incorporate exercise activities into their lifestyle.

Purchase antivert 25mg with mastercard. Headlines at 8:30: Marijuana could ease symptoms of multiple sclerosis.